Groggy and feverish with Covid-19, I began playing an online game through an avatar, Mr. Tea.

The game was similar to Wordle, popularized by The New York Times: a downmarket version apparently beyond the reach of copyright law. Wordle ritually offered one secret word—and only one—per day, but the app provided unlimited words in quick succession. This gave the game a jittery, compulsive feel, as if playing the slots at a word casino. Five empty boxes, signifying a new five-letter word, appeared seconds after the last word was revealed, obliterating it from memory as another game began. Every five minutes offered a new dawn, a new shot at greatness.

Starting words: ARISE. AMIGO.

After a few hours of solo play, I noticed that the game would match you with other players to compete in real time. Each had an avatar in the same cartoon style as Mr. Tea. They represented a variety of human types, some famous—a Frida Kahlo lookalike was popular—and some generic, like a twinkly old woman. Most players had two-word names assigned by the game: Prudent Douglas. Winsome Sarah. Sharp Felix. Wise Brad. Others, like Mr. Tea, had chosen something personally resonant. In fifteen minutes, you might play someone called ZipZap with rainbow hair, and then an Einstein lookalike called Alert Ned, and then a smiling blond youth whose starting word was HORNY or NAKED. Games went so fast that the fact that you were interacting with people who existed somewhere on Earth, living unfathomable lives in their own homes, barely registered.

Starting words: DIARY. HAIRY. FAIRY.

The pop-up ads that filled the screen every few rounds implied the strangers behind the placid-faced avatars were not well—that, realistically, they would be called Miserable Janet and Doomed Craig. Many of the ads had an unsettling quality, like an art-house film. A giant skull chewed a yellow tablet as its jaw crumbled in slow motion, hawking some kind of late-stage periodontal rinse. In another, a funereal voice urged players to join a class action lawsuit about cancer-causing toxins at a military base. One featured a medical-style drawing of an obese body, pink fat and multicolored viscera exposed. None of the advertised products were desirable; if anything, they were troubling reminders of death, decay, and the futility of all human endeavor. But after several long seconds, you could click through to the next game . . .

Starting words: FEAST. YEAST. KNEAD. READY.

Scoring was simple: If you won a game against an opponent, you earned a star. If you lost a game, one star was subtracted from your total. The overarching goal of play was to accumulate more stars, rising up through ranks until you achieved Legendary status. It was hard work racking up stars; frequently, the sequence of guesses went against you, so that if you correctly guessed four letters in your turn (—REAM), your opponent could add the last letter in his turn (DREAM) and win. Many high-star players sandbagged, making bad guesses while opponents did the work. Or maybe they were just rushed: Each turn lasted only thirty seconds. Sometimes, dazed by the rapid-fire nature of the game, I failed to guess words closely related to my own life: WRITE. WOMAN. NOVEL. Then I’d be a down a star, further from Legendary than I liked. I’d have to make it up on the next word . . .

Starting words: HOIST. MUSTY. MISTY. MOUSY. LOUSY.

At some point I got over Covid, but I kept playing the game. Not just racking up stars, I was exploring an interesting new way of being. It was sheer busywork, but maybe—after two anxious years online—that’s what was needed: a “third way” between real life and the exhausting glut of content on the Internet.

In South Korea, they were pioneering a trend called untact, eliminating human contact from transactions so as to render them hygienic and efficient. To a degree, California had gone untact: Paperless menus and self-checkout kiosks were the new normal. But the game went even further, not just obstructing human contact but draining the English language of all meaning. Mr. Tea and his brethren swam in a contact-less, content-less sea: both untact and untent. Nothing but words, words, words.

Starting words: BREAK. WEARY. WOULD. COULD. MOLDY. SPUME.

One evening after dinner—my husband watering the lawn, the kids off somewhere—I noticed Mr. Tea was earning double points for every win. It was called Happy Hour and started at 7 p.m. in California. What a fool I’d been! I should have been taking advantage of this hour all along. A loss no longer wiped out five minutes of work. Poor Mr. Tea: plodding along, winning a star here, a star there, then losing three games in a row to some random online degenerate. He deserved to put some real points on the board!

So, in late summer, Mr. Tea became a Happy Hour regular. He achieved Legendary status—a new blue banner under his name—and kept going.

Starting word: ADIEU

Where would it end? There seemed no limit to the number of points Mr. Tea could score. Occasionally, you’d see a Legendary player with 3,780 stars or 4,502 stars and feel repulsed: They had taken things too far. At some point, Clever Zachary or Audacious Bev had crossed over into a weird, uncharted realm of online gaming. Like Mr. Kurtz in Heart of Darkness, they had lost all perspective and gone raving mad:

“More stars! I must have more stars!”

“But, sir—”

“Shut up!”

I didn’t want that ghoulish fate for Mr. Tea. I had to get him out of here before this word game robbed him of his very soul.

I began casting around for an alternative: some form of methadone to wean me off the game. Nagged by a sense that I should read more Catholic novels, I placed an order for The Father’s Tale by Michael D. O’Brien. To my surprise, when the hardback arrived, it was a doorstop of 1,076 pages. I started dragging it around: to the hair salon, to school pickup. It was about a widower in rural Canada whose son falls in with a shadowy cult while studying at Oxford. To rescue his wayward boy, the widower embarks on an epic journey spanning England, Finland, and Russia.

Suddenly, I was plunged back into the world of stories: of contact and content. It bore little resemblance to the manic circus of the Internet. O’Brien seemed to live in a better place than I did—a place where a single mother of six answers the door in “a tan cardigan, white blouse, and calf-length skirt printed with small pink roses.” A place where everybody reads books and discusses them. Was this the past, or Canada, or what? At any rate, it felt restorative to linger there awhile.

Since writing Part 1 of this essay, I’ve been spending far less time with Mr. Tea.

But anytime I need him, he’s there waiting for me, with a smile.

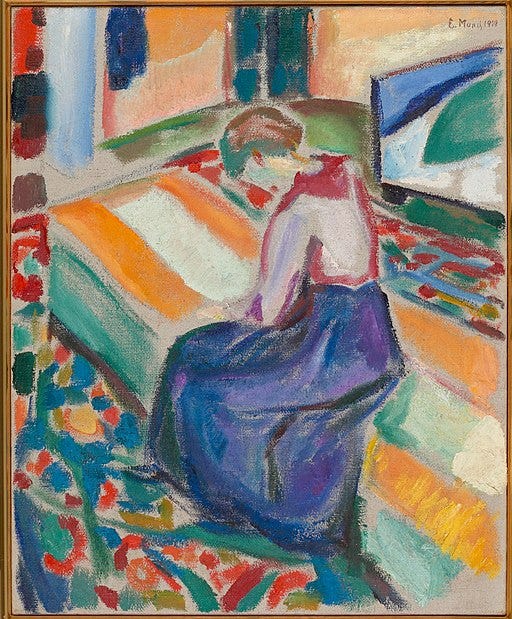

(Image: Edward Munch, Woman Seated on a Sofa, public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

A journey through different worlds of the mind packed into a pseudonym society of a game, then a book with its own journey through a world inside the world of the book, and back home to real life. Wonderful.

Damn, these two pieces launched you to warp speed right out the (star)gate.